Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery | By John Michael Vlach | University of North Carolina Press, 258 pp. illustrated

Reviewed by Greg Andoll, Assoc. AIA, NOMA

The best books on architectural history do not limit themselves to discussions of form and style. They go further by examining buildings in the broader social and cultural conditions in which they were built. In this sense buildings become artifacts through which we gain a better understanding of the past.

Often the past is not pretty. In Back of the Big House John Michael Vlach provides an unflinching picture of the Antebellum South through the study of a forgotten building genre – slave cabins and related buildings. With over 200 archival photos and drawings, Vlach creates a virtual tour of this lesser-known architectural heritage. Along the way, we gain a nuanced understanding of the lives slaves lived, the customs they practiced, and the difficulties they endured.

Back of the Big House is primarily a visual book; although it is far from the “coffee table” variety. Vlach is a Professor of American Studies and Anthropology at The George Washington University and has written extensively on African American contributions to American material culture. The book has a solid scholarly foundation while it remains free of academic jargon. He encourages the reader to thumb through the chapters (which are arranged by building types), and then read the accompanying text.This is a good approach because one is initially struck by the simple visual appeal of the buildings, and later the explanatory text makes clear the contributions slaves made to their designs.

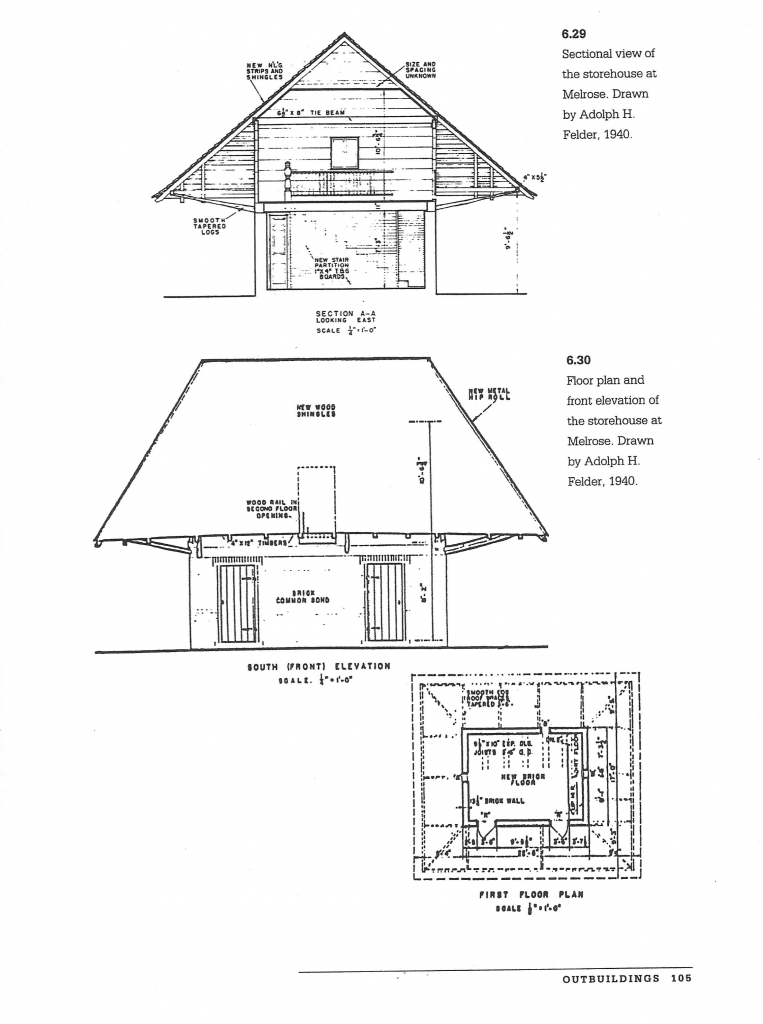

Indeed this is the main thesis of Back of the Big House. Vlach argues that because most of the labor needed to run a plantation was done by slaves, they knew best how to build or modify service buildings. And since the owner considered these buildings to be functional (hence their location at the back of the Big House), slaves were allowed some autonomy in their design. These included smokehouses, outdoor kitchens, tanneries, dovecotes, barns, icehouses, and in one instance a hospital. Far from being mere shacks, these buildings were frequently well detailed and constructed.

Vlach further argues that slaves became so possessive of “their buildings” that owners and others would not cross these unmarked boundaries, thereby providing slaves with an opportunity to develop their own culture. “… the spaces that slaves claimed and modified for their own domestic purposes provided them with their own sense of place. In these locations they were able to develop a stronger sense of social solidarity, a feeling of community that would serve as a seedbed not only for further resistance, but also for the invention and maintenance of a distinctive African American culture.” For example, in one remarkable act of defiance an African-born slave refused to have a wood floor in her cabin. “My ma never would have no board floor like de rest of ’em, on ‘count she was African – only dirt.” recalls her daughter former slave Susan Snow as recorded by the Federal Writers’ Project. Vlach explains: “By rejecting an apparent material ‘improvement’, this woman re-created in her house an aspect of African domestic life with which she was more comfortable. Whereas her master probably thought he was saving lumber and his carpenter’s time, she was subtly resisting his ownership.” (He adds, correctly, that if properly maintained, dirt floors can be as hard as concrete and are not necessarily dirty.)

Unfortunately, many of the buildings in Back of the Big House no longer exist. Vlach relied on the archives of the Historic American Building Survey for photographs and drawings. He also researched the Federal Writers’ Project for first hand interviews with former slaves. Where these two sources left gaps, he used other first-hand documents to back up his thesis – including Frederick Law Olmstead’s travel journals.

Back of the Big House is unlike any architectural history book you may read. It is refreshing in its subject matter and brings to light a unique and nearly forgotten form of American vernacular architecture. Most importantly it reminds us that everyone contributed to this country’s built landscape.

A version of this book review appeared in an earlier edition of the AIA Baltimore Newsletter.